Treasures of Heaven

One of the most popular exhibitions this summer here in London has been the Treasures of Heaven exhibition at the British Museum. The exhibition’s subtitle is ‘Saints, relics and devotion in medieval Europe’ and most of the exhibition centres upon a truly stunning collection of reliquaries. These were the exquisitely crafted containers, made to encase the relics that so often were the focus of medieval religious life. The exhibition continues until October 9th at the British Museum and I highly recommend it to you.

I was surprised by how moving I found these exhibits, these medieval devotional objects. As a child brought up in Protestant Britain I’d previously regarded relics as fake, a cheap and nasty trick played on the unsuspecting by a money grabbing church hierarchy, along with the buying of absolution for one’s sins. The reading we heard earlier on from Chaucer’s The Pardoner’s Tale from The Canterbury Tales expresses so clearly that aspect of medieval religion:

“But sirs, there’s one thing I forgot to add:

I’ve got relics and pardons in my bag

As good as anybody’s in England,

All given to me by the Pope’s own hand.

If any here should wish, out of devotion,

To make an offering and have absolution.”

Chaucer’s Host has clearly no time for the Pardoner’s wiles when he replies

“By the True Cross that Saint Helena found,

I’d rather have your ballocks in my hand

Than any relic in a reliquary

Let’s cut them off and I’ll help you carry your balls

And have them set in a pig’s turd!”

But for every crook involved in the cult of relics I now realise that there were far more people who genuinely believed in the power of saints to heal their wounds and to help them connect earth with heaven. But how did this all begin? We have to take ourselves back to the early history of Christianity, when Christians faced truly awful and cruel suppression by the Roman Empire. This still new religion, with its central symbolic figure of Christ dying on the cross to save us all, suffered many further martyrdoms – with so many leaders and followers prepared to lose their own lives for their faith. Knowing what we do of human contrariness and also of our remarkable ability to hold on to our ideals, it’s perhaps not all that surprising that the suppression of Christianity by the Romans only increased its popularity amongst at first the already suppressed and marginalised members of Roman society and later amongst a wider range of social classes.

Those early martyrs were regarded as saints and it was believed that they held the power to intercede with God on behalf of human beings. Through the bravery of their deaths martyrs were assured of a place beside Christ in heaven and so could be relied upon to speak on behalf of those humans who prayed to them. So saints could be prayed to, called upon in times of need, and their shrines and their human remains were regarded as sacred, holding great spiritual power. Once Christianity was legalised by the emperor Constantine in AD 313 the cult of saints could develop freely and it is remarkable to realise just how much power saints continued to have in northern Europe till the Reformation and still in many parts of the world to this day.

When early Christian leaders were martyred for their faith, their followers would try to rescue their bodies, which were believed to hold healing power. Jesus’ bodily ascension into heaven meant a lack of body relics but articles associated with his death abounded, such as thorns from the crown in which he was crucified, nails from the cross and the cross itself. Helena, mother of Emperor Constantine, spent much time in the Holy Land and legend tells of her search for the True Cross. Three crosses were brought to her but how could she prove which of these was the true cross? A sick woman was brought before her and when the first two crosses were shown to this woman there was no change in her health. In the presence of the final cross her health was restored and Helena was credited forever more with locating the True Cross, fragments of which were used as relics throughout the medieval Christian world.

I’ve spoken often here of the work of Alister Hardy, marine biologist and Oxford professor, and founder of the Religious Experience Research Centre. Hardy is thought to have been the first person to describe human beings not as ‘homo sapiens’ – meaning ‘thinking man’, but ‘homo religiosus’ – humanity in search of sacred meaning and connection, human beings as seekers of God, who seek connection with the divine, the transcendent, with something greater than ourselves. This search for connection with the divine is a characteristic of the earliest human beings. How can it help us to understand the seemingly bizarre faith in saints and their relics in medieval times?

It’s helpful to remember how religion must have imbued medieval life in a way it is perhaps hard to imagine today. Medieval belief systems can be described as supernatural and with only rudimentary medicine and a limited understanding of biology little wonder that they placed their faith in the healing powers of saints and their relics. People had a strong belief in an after life and in the reality of heaven and hell – therefore they needed to earn their place in heaven.

The curators of the Treasures of Heaven exhibition at the British Museum point out the significance of the use of the finest materials by the craftsmen who created the reliquaries – the use of gold and silver and precious stones conveyed spiritual values such as purity and perfection. There was also a significance of place – both shrines and reliquaries were imbued with sacred connectedness, occasionally literally it seems. One humorous medieval picture from Hereford Cathedral shows a pilgrim who has managed to clamber inside a large reliquary and is having to be pulled out, seemingly unsuccessfully, by an assortment of monks. Joseph Campbell, mythologist and writer, describes sacred space as “a space that is transparent to transcendence and everything within such a space furnishes a base for meditation…..when you enter through the door, everything within that space is symbolic, the whole world is mythologized…. This is the place of creative incubation.” No wonder that people yearn to visit and touch relics.

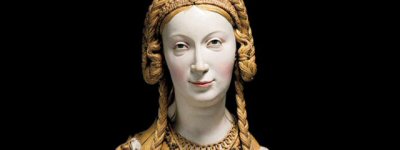

Early reliquaries were highly stylised pieces but as the centuries progressed there was a development from those stylised early reliquaries to later more human, more life-like containers. This golden head of St Eustace (in British Museum magazine) from the 13th century makes an interesting comparison with the oh so human and kindly looking woman saint, possibly, companion to the English princess Ursula, that we have on our order of service sheet today. St Ursula and her virgin companions are said to have been martyred on their way home from visiting relics in the Holy Land. This is a 16th century painted wood reliquary, which would have contained a saint’s skull. Her kindly, beatific expression must surely have given hope to those who prayed to her.

From the 12th century onwards, pilgrimage developed as an important aspect of medieval religious life, linked to the sites where relics were held. Pilgrimage became a religious requirement, sometimes as punishment or for the seeking of forgiveness for sins committed, as well as a positive activity for all to embark on at some point in their lives. Pilgrimages brought further developments – the need for something to take away from the shrine which could contain some of its power. Probably the most important English shrine of all time, and the quickest to be developed, was that of Thomas Becket at Canterbury. Monks there collected Thomas’ blood from the cathedral floor and mixed it with holy water and distributed it to pilgrims in little lead flasks. It became known as Canterbury water and was regarded as a most effective healer. On the back of one of these flasks in the British Museum is found a Latin inscription that states that ‘Thomas is the best doctor of the worthy sick.’

It’s perhaps easy to dismiss these medieval beliefs in the healing power of relics as quaint and simplistic. But part of the exhibition at the British Museum has a slide show making connections between the medieval cults of saints, relics and reliquaries and life today. Pilgrimage continues to be of considerable significance in all the world’s religions. In our own collection of writings, Kindred Pilgrim Souls, Maire Collins writes of the value she gained from following the ancient Camino de Santiago in Northern Spain and of the way it taught her to “acknowledge people I meet as fellow pilgrims on their own personal journey”.

The next major exhibition at the British Museum will focus upon the Muslim requirement of hajj, visiting Mecca at least once in a lifetime, as one of the five pillars of Islam. Buddhism, Hinduism and Judaism all have their own traditions of pilgrimage, of sacred journeying. And relics still hold great significance for some today – you might have heard of Therese of Lisieux, a Carmelite nun in the late 19th century, who was made a saint in the 1920s. Her relics are on a continuing tour of Europe – they visited Britain in 2009 and were venerated by quarter of a million people at Westminster Abbey. The singer Edith Piaf is said as a child to have been cured of blindness after a visit to Therese’s grave.

If we think of the way we sometimes treat famous celebrities in society today – rushing to catch a glimpse of them, taking photos of them and collecting memorabilia of them – sociologists describe this behaviour as the ‘cult of celebrity’ – and indeed it does seem to have links with religious behaviour of old. Those teenage posters on walls are a statement of who we are and what we value. The photos of family and friends that we admire on mantelpieces give us a sense of connection beyond ourselves, with both the living and the dead. And what of the collections that some of us make of ornaments or other objects? Some of the most interesting reliquaries are those that collect a number of tiny relics together. They are reminiscent of various artists’ work to collect small objects in cabinets and of natural history collections – all painstakingly labelled. I wonder how many of us today are wearing pieces of jewellery that hold emotional meaning and significance for us or have other objects that remind us of those we love? Richard Gilbert’s poem about the empty chair “evoking memories of those we have loved and lost” that we heard earlier on reminded me of the poignant day that I cleared the kitchen in my parent’s house and sat weeping over a Pyrex dish that held so many childhood memories for me.

(In the service people spoke of their own memories connected with objects.)

Photos, jewellery, furniture, humble kitchen objects – all these are testament both to the poignant power of our memories and to our quite remarkable human ability to impart meaning, to connect the material realm with the transcendent, to join earth with heaven. Perhaps we who live in the 21st century are not so different from those medieval seekers of relics after all, perhaps we too are seeking the comfort and connection that objects can bring.

May you live this day

Embraced by tenderness

Nourished in body and spirit

Compassionate of heart

Kind in word

Courageous in deed

Mindful in awareness

Gracious in love. Amen

Rev. Sarah Tinker

Sermon – 28th August 2011