The Maps of Our Lives

I’m strangely fond of old maps – the kinds that were drawn long before satellite images or proper surveying equipment – maps with strange creatures drawn in the seas and those evocative Latin words – terra incognita – unknown land – beckoning an explorer forwards to new adventures or perhaps warning the more wary traveller to keep away – all depending on your point of view.

Maps in times gone by were largely works of fiction. They combined hopes and myths with bits of knowledge. There’s a lovely example of such a map from south east Asia on the front of today’s order of service, combining known landscape features like rivers and mountains with mythic places marking where events in the Buddha’s life story occurred. Such maps were defined more by belief than by geography and such maps can be read – and when read they can tell us what’s important to the people who commissioned and drew them. Many medieval maps from the western world have the city of Jerusalem in a central position because people’s faith was oriented towards the so called Holy Land. In Islamic cultures you would find maps with the Holy City of Mecca at their centre.

In modern life, with the reverence we oft times give to our individual existences, we’re likely to place ourselves at the centre of the maps of our own lives. A Mulla Nasrudin story illustrates this human tendency towards self-centredness – it’s a story that resonates perhaps with the Health & Safety concerns of our own era. Nasrudin had apparently been reading that most accidents occur within two miles of our own homes and so in order to reduce his risk he moved house to a place three miles down the road.

But we can’t escape from ourselves. We are the centres of our own universe and we view the world from our own perspectives. Perhaps the best we can hope for is to become more aware of our own bias and learn not to assume that our own perspective is the only way to consider the world, learn not to assume that our own perspective is the best way to view the world.

We heard an extract earlier from a booked entitled Off The Map: (An Expedition Deep into Imperialism, the Global Economy, and Other Earthly Whereabouts), written by Chellis Glendinning – an author who describes herself as “being in recovery from Western Civilization”. She writes that “My entire education has been shaped by the defended, and banal, projections of conquest. The task now is to expand beyond the identity and experience of the empire world. It is to learn the stories so long squelched and denied: of native peoples, the vanquished, losers in war, survivors of conquest, the other side of the story. The task is to realize the culture and community that have been erased: knowledge of animals and seasons, music of the land, extended family, cooperation, celebration. The task is to remember. My people. Our history. The good and the horrendous, nothing left out, colonizer and colonized indelibly intermingled, indelibly embraced.”

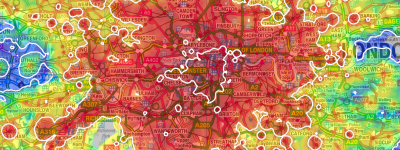

Our views of the world are shaped by matters of power, both economic and political. A simple illustration of that can be seen on maps showing the position north pointing upwards – it’s a convention on maps and it stems from the economic and political dominance once held by countries of northern Europe. On a spinning globe there is no up or down – the directions Jeannene called in at the start of today’s service move in relation to where we ourselves are on the planet, move in relation to any fixed point.

If you’re interested in exploring different forms of representation you might enjoy reading Bruce Chatwin’s book Songlines, which was my first introduction to the Aboriginal Australian view of territory where human life, history, landscape, mythology, images and songs are all combined in one network of knowledge shared by all. It’s a powerful reminder that there are many ways to view our precious world and the varied lives lived upon it.

There has to be bias in what we choose to include or exclude when making a map. A map is a physical representation of landscape but it can’t include everything because if it did then the map would be as large as the territory – we would be covered by the map. Writer and mathematician Lewis Carroll delighted in exploring such ideas – he wrote of a country’s leader who had tried out different scales of map:

“And then came the grandest idea of all! We actually made a map of the country, on the scale of a mile to the mile!”

“Have you used it much?” I enquired.

“It has never been spread out, yet,” said Mein Herr: “the farmers objected: they said it would cover the whole country, and shut out the sunlight! So we now use the country itself, as its own map, and I assure you it does nearly as well.”

And so we all survey and select in our map making and in our living. We decide what to represent and what to leave out. On your hymn sheet today there is a map – a bit like the treasure maps you may have drawn in geography lessons at school. Beside the map are some questions for you to consider and perhaps to include in a map that could represent your life:

- What mountains have you had to climb in life?

- What helps to guide your path in life?

- What do you do when you feel lost?

- What seas, real or imagined, have you enjoyed sailing? What inner journey might you like to take?

- Are there safe harbours for you in life? How might you know when it’s time for your ship to sail onwards?

- Have you known ‘stuck’ places that proved to be fruitful?

- What maps or guidebooks or other sources of information are useful for your journey of life?

And let’s not forget the idea of viewing our own bodies as maps of our lives. Remember the words we heard earlier, written by ecstatic dance practitioner Gabrielle Roth, who created the Five Rhythms as a way for us to reclaim our whole selves through movement.

She writes that “Your body is the ground metaphor of your life, the expression of your existence. It is your Bible, your encyclopaedia, your life story. Everything that happens to you is stored and reflected in your body. Your body knows; your body tells. The relationship of your self to your body is indivisible, inescapable, unavoidable. In the marriage of flesh and spirit, divorce is impossible, but that doesn’t mean that the marriage is necessarily happy or successful. So the body is where the dancing path to wholeness must begin. Only when you truly inhabit your body can you begin the healing journey. So many of us are not in our bodies, really at home and vibrantly present there. Nor are we in touch with the basic rhythms that constitute our bodily life. We live outside ourselves — in our heads, our memories, our longings — absentee landlords of our own estate.” Considering our bodies as maps of our lives, representations of our physical presence here on earth, can be a remarkably rich route towards deeper self-understanding. For every experience is in some way etched in our physical being.

A map is a guide – it can help us find our way. A map holds information for us and can pass it on to other people for their guidance. But a map is only as useful as the person reading it. I’m probably not the only one who has lost my way even with a perfectly good map in my hand – convinced that I knew where I was. So let’s remember to check our guides in life from time to time, and remind ourselves, especially when we’re sure that we’re right, that it’s worth stopping from time to time to take our bearings and have a good look round. Maybe we’re not where we thought we were after all!

Rev. Sarah Tinker

Sermon – 31st August 2014